Saturday, January 20, 2018 - 3:00pm

Saturday, January 20, 2018 - 5:30pm

Whitney Humanities Center

53 Wall St. - Auditorium

New Haven, CT

06511

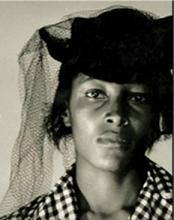

A screening of the film, The Rape of Recy Taylor, (91 minutes), will be held on Saturday, January 20, 2018, at the Whitney Humanities Center., from 3-5:30pm. Following the film, Yale historian Feimster, who serves as a contributor in the film, will moderate a Q&A with its director Nancy Buirski.

On the night of September 3, 1944, in Abbeville, Alabama, six white men kidnapped Taylor at gunpoint as she walked home from church, blindfolded her and raped her. After Taylor reported her assault to Abbeville law enforcement, her and her extended family’s homes came under a series of attacks. Meanwhile, the Abbeville legal system worked instead to protect her assailants. The town’s sheriff asked Taylor to keep silent about the crime while a grand jury refused to hand down indictments.

[Recy Taylor’s] was a story white, mainstream media outlets initially ignored. In their place, it was black-owned newspapers which sounded the first alarms about the cover-up in Abbeville and would eventually focus countrywide pressure on Alabama’s governor to act.

Rosa Parks, who was already well-known as an NAACP activist, came to Abbeville to organize on Taylor’s behalf and raise her profile.

As a work of restoration, Buirski’s documentary, which is based on the 2010 book “At the Dark End of the Street” by Danielle McGuire and premiered at the Venice film festival, also offers an antidote to the sanitized concept of Rosa Parks that persists today.

“She didn’t come out of nowhere,” Crystal Feimster, tells Buirski’s audience. Rather, Parks was a practiced fighter on behalf of black women facing sexual violence, and she was vocal about the role white predation had played in her own life. In 1944, Parks’ reputation was fearsome enough that the sheriff removed her from town several times, at least once, with force.

But for all of the attention her cause received, justice eluded Taylor. Her rapists confessed but were buffeted to freedom by a form of racism with especially strong components of history and blood. Members of the all-white grand jury that refused – a second time – to issue indictments shared familial ties to her rapists. Taylor’s extended family shared a last name with the sheriff because his ancestors enslaved hers. When the sheriff asked for Taylor’s silence, he was merely putting history on repeat.

In parsing the outcome, Buirski said she wanted her audience to see sexual violence in all of its political dimensions.

Sponsors: Department of African American Studies, African American Cultural Center, American Studies Program, Women’s, Gender, Sexuality Studies Program, Film and Media Studies Program, History Department, Yale Center for the Study of Race Indigeneity, and Migration, Public Humanities at Yale, and Films at the Whitney, supported by the Barbakow Fund for Innovative Film Programs at Yale

203-432-1177

Contact email:

lisa.monroe@yale.edu